New theorem helps reveal tuberculosis’ secret

Uncovering missing connections in biochemical networks

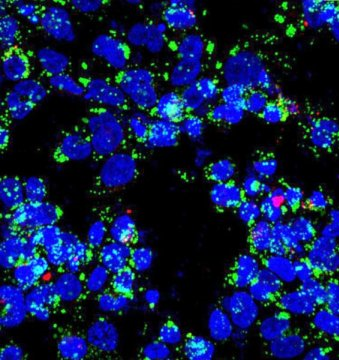

Upon infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli (labeled in red), macrophages (nuclei stained blue) accumulate lipid droplets (green). The network controlling the expression of an enzyme that is central to bacterial metabolic switching to lipids as nutrients during infection is the topic of a new paper by researchers at Rice and Rutgers universities.

Credit: Emma Rey-Jurado/Public Health Research Institute

A new methodology developed by researchers at Rice and Rutgers universities could help scientists understand how and why a biochemical network doesn’t always perform as expected. To test the approach, they analyzed the stress response of bacteria that cause tuberculosis and predicted novel interactions.

The results are described in a PLOS Computational Biology paper published today.

“Over the last several decades, bioscientists have generated a vast amount of information on biochemical networks, a collection of reactions that occur inside living cells,” said principal investigator Oleg Igoshin, a Rice associate professor of bioengineering.

“We are beginning to understand how these networks control the dynamics of a biological response, that is, the precise nature of how a concentration of biomolecules changes with time,” he said. “But to date, only a few general rules that relate the dynamical responses with the structure of the underlying networks have been formulated. Our theorem provides another such rule and therefore can be widely applicable.”

The theorem uses approaches from control theory, an interdisciplinary branch of engineering and mathematics that deals with the behavior of dynamical systems that have inputs. The theorem formulates a condition for an underlying biochemical network to display non-monotonic dynamics in response to a monotonic trigger. For instance, it would explain the expression of a gene that first speeds up, then slows down and returns to normal. (Monotonic responses always increase or always decrease; non-monotonic responses increase and then decrease, or vice-versa.)

The theorem states that a non-monotonic response is only possible if the system’s output receives conflicting messages from the input, such that one branch of the pathway activates it and another one deactivates it.

If a non-monotonic response is observed in a system that appears to be missing such conflicting paths, it would imply that some biochemical interactions remain undiscovered, Igoshin said.

“What we do is figure out the mechanism for a dynamic phenomenon that people have observed but can’t explain and that seems to be inconsistent with the current state of knowledge,” he said.

The theorem was formulated and proven in collaboration with Eduardo Sontag, a distinguished professor in the Department of Mathematics and Center for Quantitative Biology at Rutgers. Sontag focuses on general principles derived from feedback control analysis of cell signaling pathways and genetic networks.

The researchers applied their theory to explain how Mycobacterium tuberculosis responds to stresses that mimic those the immune system uses to fight the pathogen. Igoshin said M. tuberculosis is a master in surviving such stresses. Instead of dying, they become dormant Trojan horses that future conditions may reactivate.

According to the World Health Organization, a third of the world’s population is infected by the tuberculosis bacteria, though the disease kills only a fraction of those infected.

“The good thing is that 95 percent of infected people don’t have symptoms,” said Joao Ascensao, a Rice senior majoring in bioengineering and first author of the paper. “The bad thing is you can’t kill the bacteria. And then if you get immunodeficiency, due to HIV, starvation or other things, you’re out of luck because the disease will reactivate.”

Ascensao said M. tuberculosis is hard to grow and work with in a molecular biology setting. “A generation of E. coli takes 20 minutes to grow, but for M. tuberculosis, a generation takes from 24 hours to over 100 hours when it goes latent,” he said. “So even though we have this really sparse data, the theory allowed us to uncover what’s happening behind the scenes.”

The study was motivated by a 2010 publication by Marila Gennaro, a professor of Medicine in the Public Health Research Institute at Rutgers, and Pratik Datta, a research scientist in her lab, who are also co-authors of the new paper. Their results showed that as M. tuberculosis gradually runs out of oxygen, the expression of some genes would suddenly rise and then fall back. They characterized the biochemical network that controls the expression of these non-monotonic genes, but the mechanism of the dynamical response was not understood.

“It didn’t make sense to me intuitively,” Igoshin said. “At first I couldn’t prove it mathematically, but then Sontag’s theorem allowed us to conclude that some biochemical interactions were missing in the underlying network.”

Ascensao and Baris Hancioglu, then a postdoc in Igoshin’s lab and now a bioinformatics specialist at Ohio State University, built computer models and ran simulations of oxygen-starved M. tuberculosis. Their results suggested a few possible solutions that were tested in the follow-up experiments by Gennaro’s group.

Eventually the simulations predicted a new interaction that could explain the dynamics of the glyoxylate shunt genes that control the metabolic transition network known to be important to the bacteria’s virulence.

“Researchers found that the hypoxic (oxygen-starved) signal would lead bacteria to switch from one type of food to a different type of food,” Igoshin said. “They used to eat sugars, but they’d start eating the fat accumulated inside of infected macrophages, a type of immune cell. It looks like this switch might be associated with going from an active bacterium to a latent, dormant bacterium that’s stable and doesn’t cause any symptoms.”

The researchers argued that the stress-induced activation of adaptive metabolic pathways involving glyoxylate genes is transient, increasing only until there’s enough of the protein present to achieve stability. “If these hypotheses are correct,” they wrote, “drugs blocking negative interactions responsible for non-monotonic dynamics could in principle destabilize transitions to latency or trigger reactivation.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers used the National Science Foundation-supported supercomputing resources administered by Rice’s Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology.

0 Comments